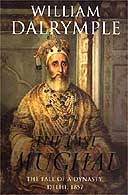

The company’s transition from trade to conquest has preoccupied historians ever since Edmund Burke famously attacked it as a “state in the disguise of a merchant”. The difference between these two images is the distance travelled by William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy, a graphic retelling of the East India Company’s “relentless rise” from provincial trading company to the pre-eminent military and political power in all of India. He hands a Qur’an to a white-bearded Sufi, a pious gesture that doubles as a majestic snub: pressed into a lower corner is none other than James I, an overlooked supplicant, depicted in three-quarter profile, “an angle reserved in Mughal miniatures for the minor characters”.

A contemporary painting by the Mughal master miniaturist Bichitr shows a supersized Jahangir on his throne, bathed in a halo of blinding magnificence. But the arrival of the British in India in the early 1600s looked very different at the time – and from the other side.

The penultimate scene travels to India in 1614, where the Mughal emperor Jahangir receives an ambassador from King James I, on a mission to promote trade with the newly chartered English East India Company.įrom the hindsight of the 1920s, this embassy looked like a key step in the building of a British imperium that would end with Britain’s monarchs as India’s emperors. A bout a century ago, a series of giant murals was unveiled in the Palace of Westminster depicting the “ Building of Britain”, which bounded in eight set-pieces from King Alfred’s long-ships beating back the Danes in 877 to bewigged parliamentarians presenting Queen Anne with the articles of Union in 1707.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)